How does China's system really work? Renowned scholar Zhang Weiwei explains the 'China model'

How do China's government, political system, and socialist market economy work? How does it see democracy? Prominent Chinese academic Zhang Weiwei explains in this sit-down interview with Ben Norton.

How do China's government, political system, and socialist market economy actually work? How does China see democracy, the USA, and Donald Trump's trade war?

Renowned Chinese scholar Zhang Weiwei (张维为) explains the China model in this sit-down interview with Geopolitical Economy Report editor Ben Norton.

Video

Podcast

Transcript

(Highlights)

ZHANG WEIWEI: From a Chinese point of view, we need to have an overall balance between political power, social power, and the power of capital, in favor of the majority, the vast majority of the Chinese population.

In the United States, it's a balance power in favor of the power of capital. That's the problem.

…

And, you see, eventually the [international] system may be increasingly in goods, in the trade of goods, more and more use of the Chinese currency; but in the trade of financial products, more and more US dollars.

There could be different layers of operations. That could be another way out.

BEN NORTON: So you would see this as part of China's vision of a more multipolar world?

ZHANG WEIWEI: That’s my vision. Because this is inevitable. Multipolarity is already there, but what we need is a multipolar world order.

This is still in the making … whether there will be something better than this system.

The problem with Donald Trump is he does not want this system either — unipolarity, the United States’ economy is hollowing out. He's not happy.

He says we should abandon that. But he looks backward.We look forward.

He says, “Let's go back to the 19th century, and mercantilism. That’s better”. For us, this is not good.

BEN NORTON: China is moving into the future.

ZHANG WEIWEI: In a way, in many ways, it’s true, yeah.

(Full interview)

BEN NORTON: Today, I have the pleasure of being joined by the renowned Chinese scholar Zhang Weiwei (张维为).

He is a professor at the prestigious Fudan University in Shanghai. He has millions of followers on Chinese social media.

And we just participated in an academic conference, and I will be speaking with him.

张老师,很高兴认识您。(Professor Zhang, it is nice to meet you.)

I want to begin asking you about your idea of the “China model”. This is something you have been speaking about for many years, for almost 20 years now.

If you look at China's economic development in recent decades, it's amazing. The statistics don't lie.

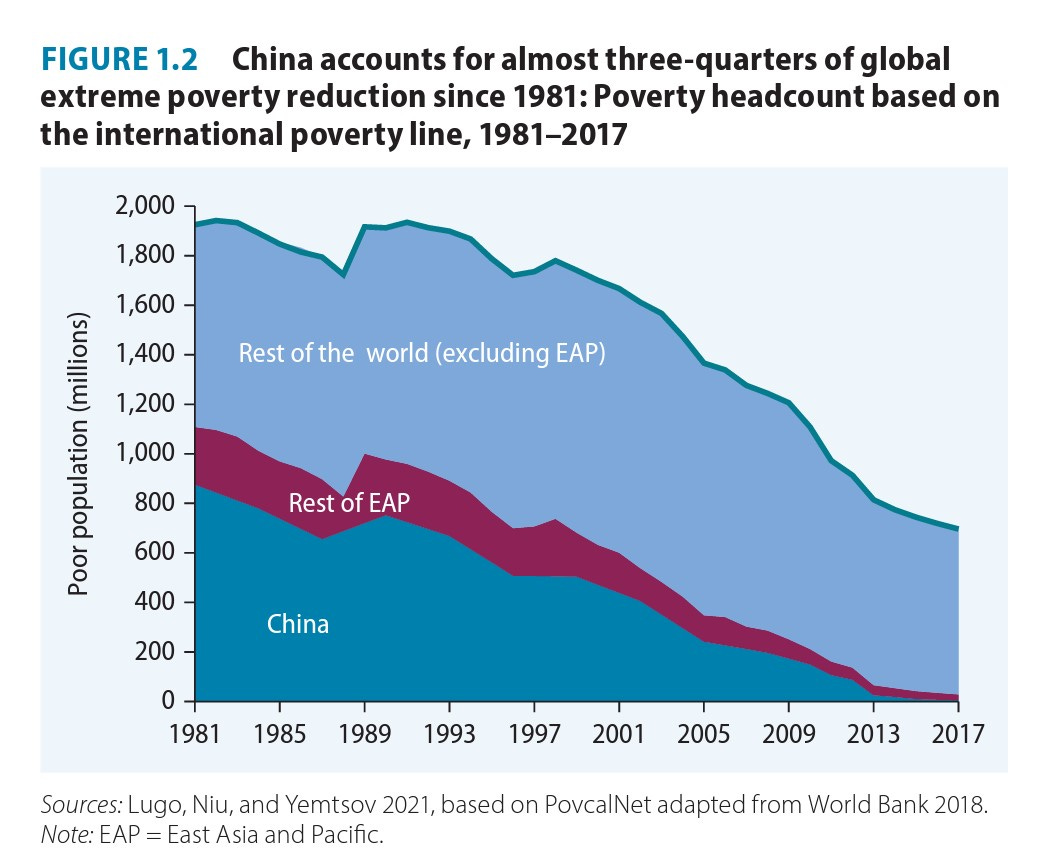

China lifted nearly 800 million people out of extreme poverty. And according to the World Bank, China is responsible for three-quarters of global reduction in extreme poverty.

China has gone from being one of the poorest countries in the world to having the largest economy on Earth, when you measure its GDP at purchasing power parity (PPP).

And China has a unique model; it describes it as a “socialist market economy”, or “socialism with Chinese characteristics”.

Can you talk about the way you see the China model, and how China has been able to combine the best part of state planning and socialism with a market economy, and has been able to balance the forces of the people and the forces of the market?

ZHANG WEIWEI: If you think of the Chinese model, or the China model, in terms of the political dimension, economic dimension, and social dimension, I can give you a very quick and simple explanation.

Politically, it is about the holistic political party.

In the Western model, political parties are partial interest parties, or partisan interest parties.

And this is serious, because China is a civilization-state, which means it’s an amalgamation of hundreds of states into one over its long history.

China was first unified in 221 BCE. Since then, for most of the time, China was ruled by a unified union. Otherwise, the country would disintegrate.

Yet behind this unified union is a system of what you may call the civil-servant examination system, which was created by the Chinese.

So China’s system today is a continuation and evolution of that system.

The Communist Party of China is a holistic interest party. And behind this is a vigorous process of what I call “selection plus election”.

Selection from China's own tradition. You have to pass all kinds of exams and tests today; your work experience, your performance. And elections for the best.

So as a result, China produces far more competent leaders than is the case in the Western models.

If you look at China’s top national leaders, the top seven, the Standing Committee members of the CPC, most of them served three terms as the number one of a province, party secretary, or governor. So they have literally governed over 100 million people before they came to the current position.

So this is important.

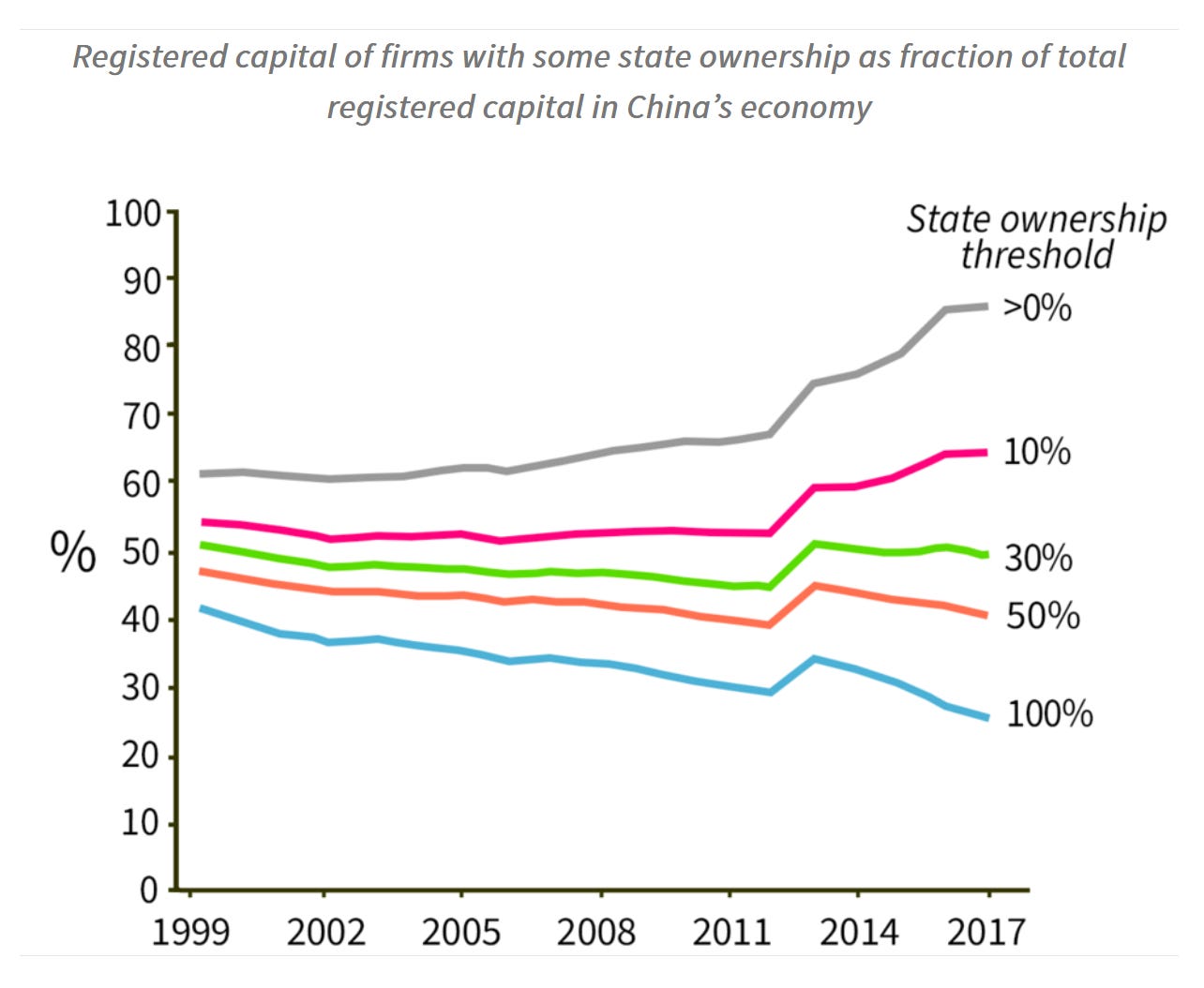

Second, economically, we call it a socialist market economy.

In fact, it is a kind of mixed economy. But many countries also have a mixed economy. But the Chinese one is unique.

It means the state owns so many resources, from minerals to land, everything. Yet, the right to use the land is flexible. It's very often shaped by market forces.

A good example of why China can be so successful in internet applications, even for those apps used in the United States, such as TikTok, Temu, or Shein.

They are Chinese inventions, because it came from internal competition within China. And after this, they become very competitive internationally.

So if you look at the Chinese internet applications, the whole digital infrastructure is created by the state sector.

Each and every village must have 4G and 5G. I told my French friends, I said that, if you go to Tibet or Xinjiang, there, you find the internet connections are better than in central Paris. Indeed!

Because this is a political task. You have to fulfill that. Even a village might have 4G, if not 5G, at least 4G.

At the same time, the private sector, like Alibaba Group, made the best use of this availability of top-notch infrastructure, to provide internet services and e-commerce to the best of their capability.

Also, as a civilization-state, the huge size matters a lot. Which means, sometimes I think, maybe China is the only type of country that can practice a real market economy, with full competition.

In China, we say 卷 (juǎn), which means competition, competition, competition.

They have 100 automobile plants that produce EVs [electric vehicles]. So those who are successful are extremely competitive. And then costs go down.

Socially, rather than the Western model of pitting society against the state, China is a state and society engaged in mutually positive relations.

You look at the Chinese state, and the party, it is far more reactive to whatever, you know, events, or incidents, or earthquakes. Whatever happens in China, the response is much faster in the Chinese model.

BEN NORTON: Can you talk more about the differences between the US capitalist model and the Chinese socialist model?

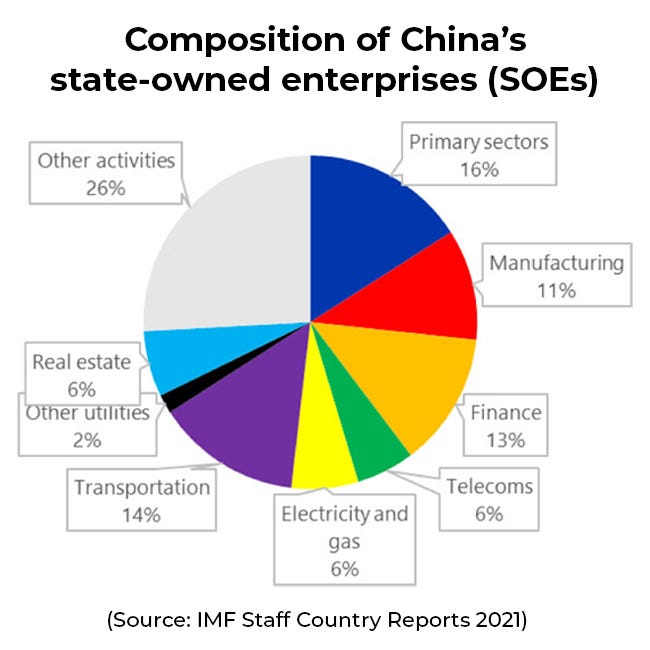

You mentioned that, in China, many of the leading industries are run by state-owned enterprises, including, the financial sector, telecommunications, certain industries, mining, energy, the land.

And another aspect of that is that, in China, there are very rich people, there are billionaires, but they have no political power.

Whereas in the United States, we can see very clearly that powerful billionaires have significant political influence, through lobbying, through funding the campaigns of politicians.

That would never happen in China.

Can you talk about what you see as the differences between the US capitalist system and the Chinese socialist system?

ZHANG WEIWEI: The American model is known for the so-called separation of powers; the executive, judicial, and legislative; and they are balanced, or whatever.

But from a Chinese point of view, these three branches all belong to the political domain. So you have a balance of power within the political domain.

The Chinese believe, from my research, that we need to have something go way beyond the political domain. We need to have an overall balance between political power, social power, and the power of capital, in favor of the majority, the vast majority of the Chinese population.

So that's a key difference.

So from Chinese point of view, in the Chinese model, you have this kind of balance of three powers, in favor of most Chinese people.

In the United States, it's a balance power in favor of the power of capital. That's the problem.

And that’s a problem in many countries.

For instance, if we make any calculations, if a US company, like Microsoft or Apple, invests in China, they make huge profits from China.

We made a rough calculation; Chinese workers maybe get 5% of the total profits. 95% go to either Microsoft, or Apple, or other intermediaries of foreign companies, not Chinese companies.

It could be 5% or 10% is China's gain. But even with that, we sell more, we create jobs, and then these workers can afford a better life than before.

Of course, China also moves up in the value chain. You cannot always only do the manual labor and produce t-shirts.

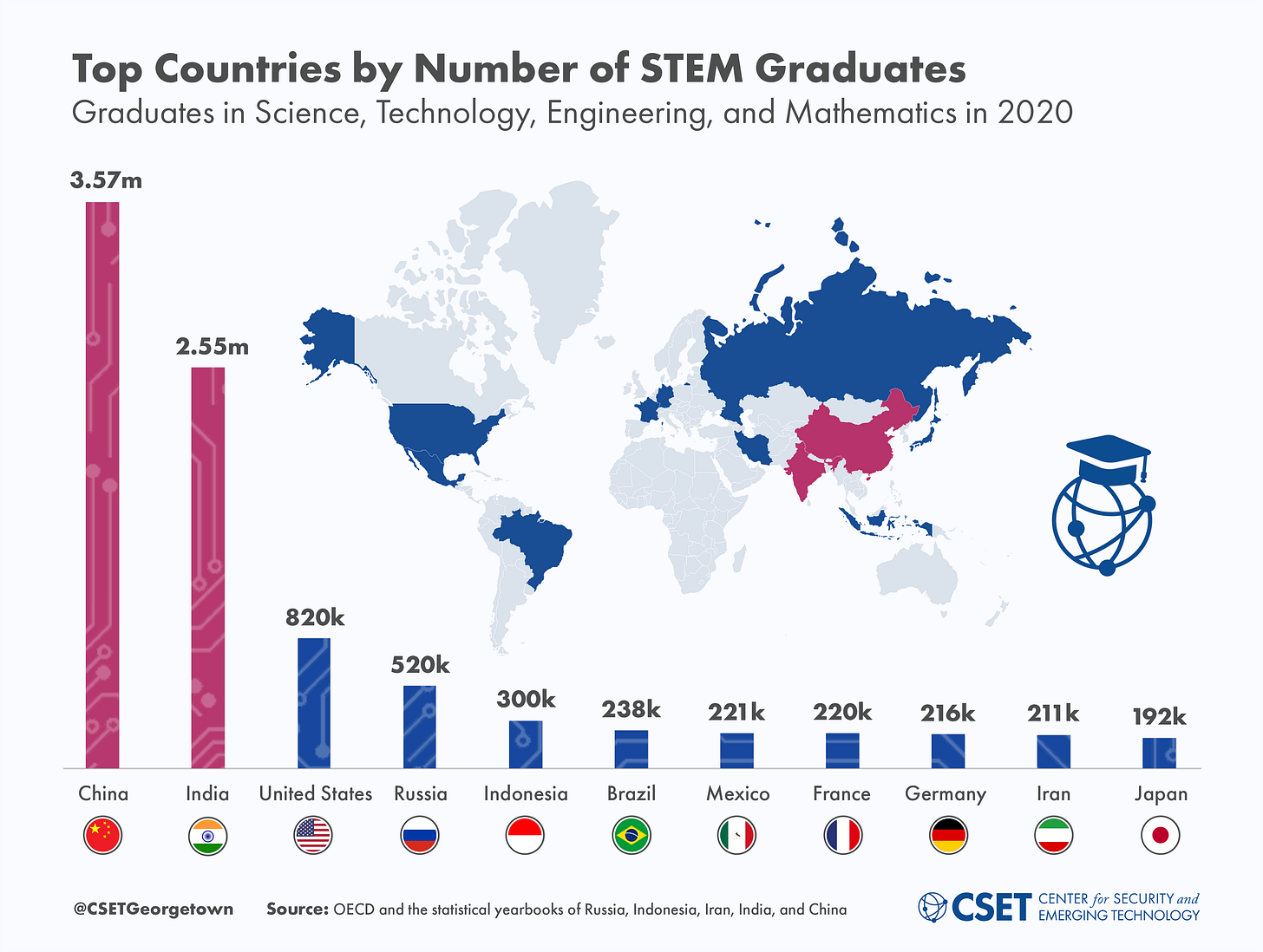

And the Chinese have, the Chinese civilization-state, every year, now produces more engineers and scientists than the Western countries combined.

That makes all the difference.

Plus this balance of power, three powers, for the whole, beyond the political domain, social power, the power of capital, and political power, in favor of most of the population. That's key.

If the United States’ companies have made huge profits in China, then they are beneficiaries of globalization.

But for one reason or another, their revenue, their income cannot be slightly more fairly distributed in the United States. And that's the problem with the US.

It's an internal problem, rather than a problem from China, from our point of view.

BEN NORTON: Can we talk about the Chinese conception of democracy?

Because a key part of what you call the Chinese model is a different conception of democracy.

Now, the very superficial understanding of democracy in the West essentially means that, every 4 or 5 years, people go and vote for a candidate who is funded by big corporations. And that's the limit of democracy. There is no popular participation.

The Chinese understanding of democracy is much deeper. In China, you have the idea of “whole-process people's democracy”, that democracy is a long process.

In the West, they say China is “authoritarian”. But you would argue that, actually, China has a different kind of democratic system. What is that?

ZHANG WEIWEI: You know, I challenged, many, many years ago, this whole paradigm of so-called “democracy versus autocracy”, “democracy versus authoritarianism”.

The problem with that paradigm, or old-fashioned paradigm, is that it is defined by the West. It's like, you know, the West, for one reason or another, first registered this particular brand.

So in China, you can explain whatever, it does not make much of a difference. You're always defensive.

So I said we need to have a paradigm shift. What I advocated is a paradigm of good governance versus bad governance.

The people who challenged me said, “Well, why do you not discuss democracy?” I said, no problem, because we divide democracy into procedural democracy and substantive democracy.

So when you talk about a regular election; a multi-party system; one person, one vote; that's procedural democracy, or democracy in form.

What we should discuss more is, first of all, democracy in substance, the very purpose of democracy.

In China, we say 道 (dào) and 术 (shù). 道 (dào) means overall purpose. 术 (shù) means specifics,or procedures.

So the 道 (dào) must be very clear. And good governance, the 道 (dào), is the very purpose of democracy.

So China first focuses on the 道 (dào), on the purpose of good governance, and how to achieve good governance. Then we try to work out the procedures and democratic practice.

You mentioned whole-process people’s democracy. A good example is how to make the legislature to produce laws.

In the United States, it's really confined to small circles, and lobby groups, and lawyers.

In the case of China, each and every major law must first go to the grassroots, hundreds of what are called the legal local contact centers, from the People's Congress.

As an example, in Shanghai, we visited one such center.

The People's Congress sent a first draft of its legislation, the law against family violence. And then they had the center organize the discussion of this draft with ordinary people.

They have kind of, I don’t know, 300 connected households. Others will give feedback.

So one piece of feedback is, in this draft, you only mentioned the husband’s violence against the wife. Well actually, especially in the Chinese countryside, there are other problems, like young people’s violence against the elderly. So this should be reflected in the law.

In the end, this is reflected. So this is what we call whole-process people’s democracy.

Then, after that, it's not just the legislation adopted; it's about enforcement.

There will be all kinds of, you know, groups from the People's Congress, from the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), which examined whether the family law has been implemented.

So the Chinese are much more serious about this.

Of course, we have our problems. Yet, on the whole, this part of Chinese democracy is not well understood by the outside world.

Another example is how we produce five-year plans.

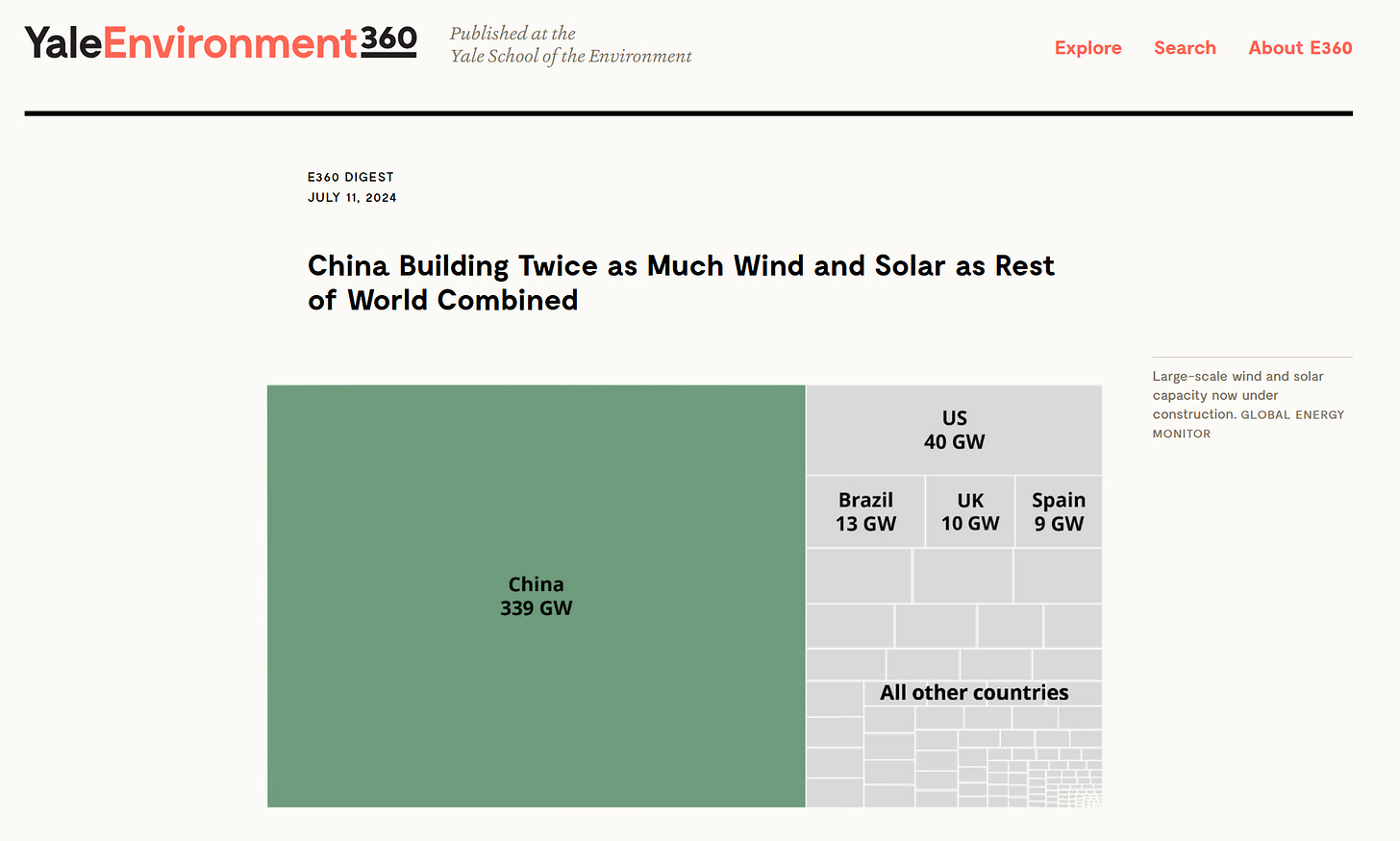

If you look at China’s progress in EVs [electric vehicles] — and it is the leader in the world in the EV industry — it's the result of four five-year plans, you know, for 20 years.

So why I consider the China model a better option than the Western model, for one thing, if we talk about the “Green New Deal”, or “Green Revolution”, there’s so much fanfare in the West, especially in Europe, you know, but even up to today, there is not much achieved.

In China, it’s completed. It's done, with the Chinese model, with 20 years of solid work. From one one-year plan, the second five-year plan, the third five-year plan, and then, executed, done.

So to what extent can the Western model produce a green transition and fight climate change?

In our model, we can do it. In the Western model, it is difficult.

BEN NORTON: Professor Zhang, back in 2011, you participated in a debate with Francis Fukuyama, who was a defender of the Western capitalist system of liberal democracy.

He famously argued, after the fall of the Soviet Union, that it was the “end of history”, and that all countries would eventually adopt this model of liberal capitalist democracy.

He claimed that there would be an “Arab Spring” in China, and you were skeptical.

You actually argued that the Chinese system would last longer, and that the US system faced many flaws, including the danger of what you called “simple-minded populism”.

Here we are, 14 years later, and I have to say, it seems like you were you were the one who won that argument.

Can you reflect on that debate and what you think about the situation today?

ZHANG WEIWEI: You know, when the debate occurred, that was in June 2011. That was the time of the Egyptian Spring, and Mubarak fell from power.

So, Professor Fukuyama was convinced that China may also go through its own “Arab Spring”.

Because, for his thesis of the “end of history”, every country’s people demand freedom of speech; for one person, one vote; so why not the Chinese?

And, I said, be cautious. I know the region. I have been to Egypt three or four times already. I said the Egyptian Arab Spring will become a Winter. I said, very firmly, I said, I have no doubt it will occur.

And, in the end, it occurred. If you tell this to the Arab people, they will say it's true; it's a winter.

It's far more complicated than these idealistic “end of history” advocates say.

I said it’s bound to fail.

The same with China. It's much more complicated; it is a civilization of thousands of years. You have to understand this.

Otherwise, whatever your prescriptions, they will not work.

Also, my debate with him was about populism. He thinks, you know, with the American media, the “free media”, freedom of speech; and he said, I remember the famous saying from Abraham Lincoln: “You can deceive some of the people some of the time, but not all of the people all of the time”.

I said, this is a bit romantic. You know, as we are in politics, we have to be very honest, because there is a huge opportunity cost.

Professor Fukuyama had this problem.

If you look at the his forecast about the Ukrainian crisis, the Ukrainian war; about Covid; about the [2024] election between, the competition between Kamala Harris and Donald Trump; he made all the wrong forecasts.

You can check it. This record will not convince.

I think he should, you know, one day come to see the limitations of his thesis.

BEN NORTON: I think in many ways he actually has recognized the limitations.

Let's talk briefly about the trade war that the US has been waging against China.

It was started by Trump in 2018, in his first term, but it was continued by Joe Biden. It's bipartisan.

And Trump, in his second term, expanded it again. It has been going back and forth.

But you have been warning that, in the US, a lot of these officials are overestimating how powerful the US is.

You know, there's this famous slogan; Trump says, “We have all the cards”; and China says, “We made the cards”.

You know, China manufactures everything; the US economy has deindustrialized.

So you have warned that, in reality, the US economy is more dependent on Chinese production than China is dependent on exporting to the US market.

How do you see the trade war? And which side is losing?

Maybe both sides are losing, but which side do you think will lose more?

ZHANG WEIWEI: Oh, the United States will lose more, for sure.

From day one, so seven years ago, when Donald Trump launched his first round of the trade war, I said openly to the Chinese audience on TV, I said the United States will suffer.

The way we see it, the United States depends far more on China, which means, if you look at the manufactured goods used by the Americans, those imported from China, either China is the only exporter and producer, or at least 80% or 90% of the components are produced in China.

In other words, the US can't find alternatives in the foreseeable future; not in one, two, or three years.

So this is the base, whether it’s an item as small as a screw, a toaster, to something as big as the frame, whatever, all kinds of heavy machine equipment.

And then, Trump's idea that, with this kind of tariff war, the US will rebuild its manufacturing industry, it’s also naive.

If you look at what we call, in this region, Shanghai, it's called the Yangtze River Delta — and the same with the Pearl River Delta — a company like Apple, or Microsoft, or Tesla, you can find all the spare parts, supplies, the whole ecosystem within a radius of 100 kilometers. All of it.

So this kind of ecosystem has been built by the Chinese through both planning and also the market, the Chinese model, over decades. It’s a product of decades.

So the United States cannot reproduce this; it’s impossible. You don’t have this kind of ecosystem.

As a result, you want to recreate it. It will take decades and decades, if not more.

So I think it’s very naive to make this kind of calculation.

And this is one reason why we say the United States will lose, and lose miserably.

BEN NORTON: The final question I have today is about the financial system, and the role of the US dollar.

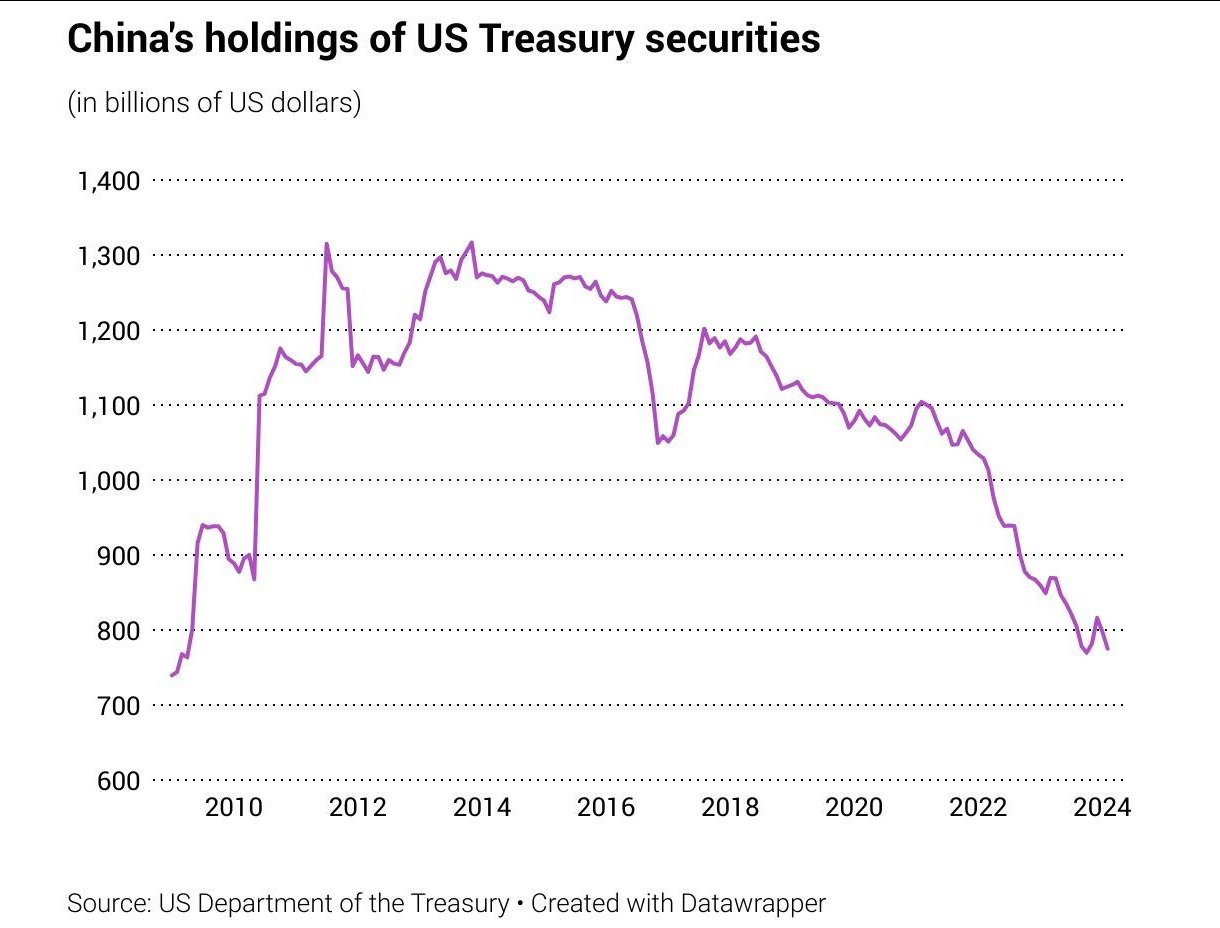

China, gradually, for the past decade, has been reducing its holdings of US government debt, US Treasury securities.

And China is part of a global movement seeking alternatives to the dominance of the US dollar and US financial hegemony.

China is part of BRICS, and it is working with other countries to create alternatives.

So what do you see as the future of the global financial system?

And how do you think that China can work with the rest of the Global South, in organizations like BRICS, to create alternatives to US financial hegemony?

ZHANG WEIWEI: You know, when the Ukrainian war occurred, the United States and the West applied hugely punitive sanctions against Russia, yet, the ruble has survived.

Because I summarize the Russian approach — I call, you know, the Chinese discuss the word “currency”, a currency war.

Currency, in the Chinese language, it’s two words: 货 (huò) and 币 (bì); which means “goods” (货) and “money” (币).

So Russia succeeded in turning this currency war into a war between goods and money.

The West has money; the US has money. But Russia has goods.

The same with China. China has manufactured goods. The US has money.

So over the long term, we believe, definitely, those with goods are in a more solid position, especially in times of crisis.

You know, this is, as China’s civilization state, if you explain this, everyone understands.

And then, the United States has weaponized everything, including dollars, including SWIFT [the interbank messaging system].

So, as a result, people look for alternatives. And the pace of this is faster and faster.

If you look at the use of CIPS, the Chinese digital payment system, it's already growing fast. I checked the data for March of this year (2025).

The Chinese companies using Chinese currency to do business are already 54%, versus the US dollar at 41%.

So, in fact, this CIPS vis-à-vis SWIFT, they represent two highways.

SWIFT is the old highway; it's old fashioned; it's based on the telegram; it takes days, three days at least, to make a deal; it charges a lot of fees.

CIPS represents a brand new highway, no loopholes, high-tech blockchain technology; and one deal takes one second, or two seconds; there’s basically no charge.

Obviously, more and more people will start to use CIPS. This is very, you may say it's a bit frightening to the US, or whatever, to certain circles, to their financial system.

But it’s inevitable, because, again, it represents another type of technology, another type of idea.

CIPS is far more socialist — no cost, or very low cost, and very efficient — compared with SWIFT, which is a monopoly, and charges a lot.

So they’re two different approaches.

Of course, if you look at the use of dollar in the world today, it's still used far more than the Chinese yuan, our currency.

Yet, if you look at trade in goods, the Chinese currency is already moving fast.

Of course, for the capital markets, capital goods, whatever, for the financial market, that's another story. China is always very cautious about that.

You see, eventually the [international] system may be, you know, increasingly, in goods, in the trade of goods, more and more use of the Chinese currency; but in the trade of financial products, more and more US dollars.

There could be different layers of operations. That could be another way out.

BEN NORTON: So you would see this as part of China's vision of a more multipolar world?

ZHANG WEIWEI: That’s my vision.

Because this is inevitable. Multipolarity is already there, but what we need is a multipolar world order. This is still in the making. And hopefully this is —

I always say, you know, Russia is a revolutionary; it wants to overthrow the American-dominated system.

China is a reformer; we see that the system has both strengths and weaknesses. We should make best use of the strengths to reduce, as much as possible, the defects. We try to reform it.

The difference between China and Russia is revolutionary or reformer.

But the common ground between the countries is we all look into the future, whether there will be something better than this system.

The problem with Donald Trump is, he does not want this system either — unipolarity, the United States’ economy is hollowing out. He's not happy.

He says we should abandon that. But he looks backward; we look forward.

He says, “Let's go back to the 19th century, and mercantilism. That’s better”. For us, this is not good.

BEN NORTON: China is moving into the future.

ZHANG WEIWEI: In a way, in many ways, it’s true, yeah.

BEN NORTON: Well, I think that's a good note to end on.

张老师,谢谢您。(Professor Zhang, thank you.)

ZHANG WEIWEI: Thank you.

BEN NORTON: I was speaking with the renowned Chinese Professor Zhang Weiwei.

Thank you so much for joining me.

ZHANG WEIWEI: Thank you, Ben.Thank you very much.

Brilliant dialogue. Well prepared interview and clear responses. Thanks.

And thank you Ben Norton for this very enlightening interview with the most intelligent and cautious {rpfessor Zhang WeiWei. Your background in economics is put to such good use in this interview. Thank you again.