Corporate landlords are taking over society, making life unaffordable: Economist Michael Hudson explains why

Private equity funds are buying up homes across the US and West, driving up rent and costs of living. Economist Michael Hudson explains how corporate landlords are a result of financialized capitalism

Private equity funds and other Wall Street investors are buying up homes across the US and the West, driving up rent and the cost of living.

Economist Michael Hudson explains how these corporate landlords are a result of the system of financialized capitalism, dominated by an unproductive rentier class. He is interviewed by host Ben Norton.

Video

Podcast

Transcript

(Introduction)

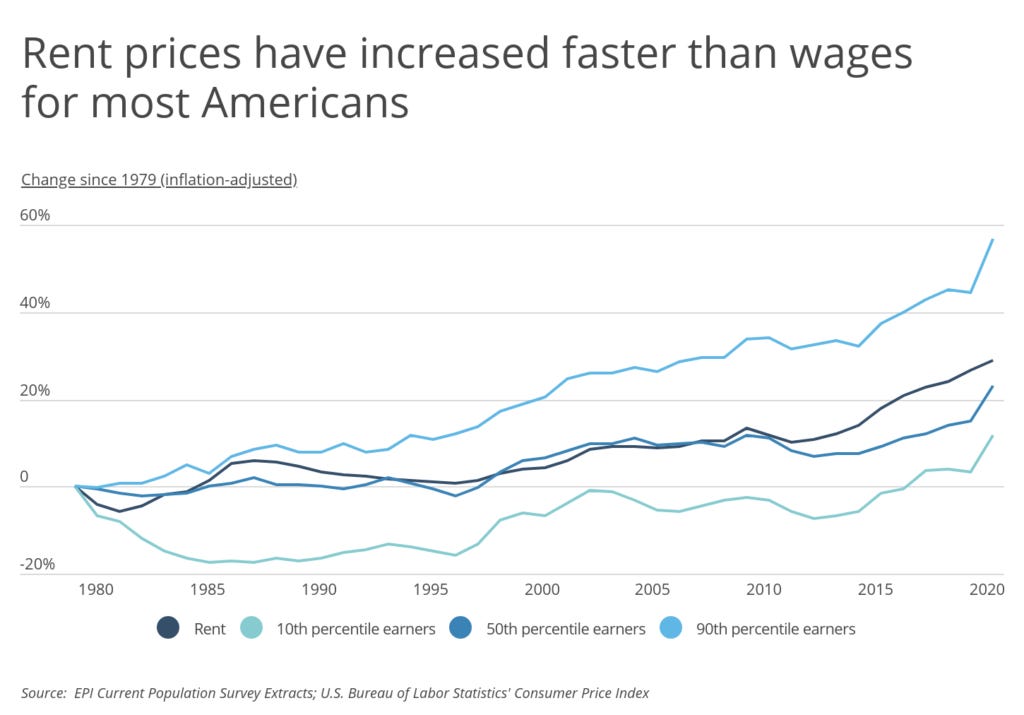

BEN NORTON: Landlords are taking over society. For many average working people, it has become impossible to buy a house. And the cost of renting housing has become prohibitively expensive.

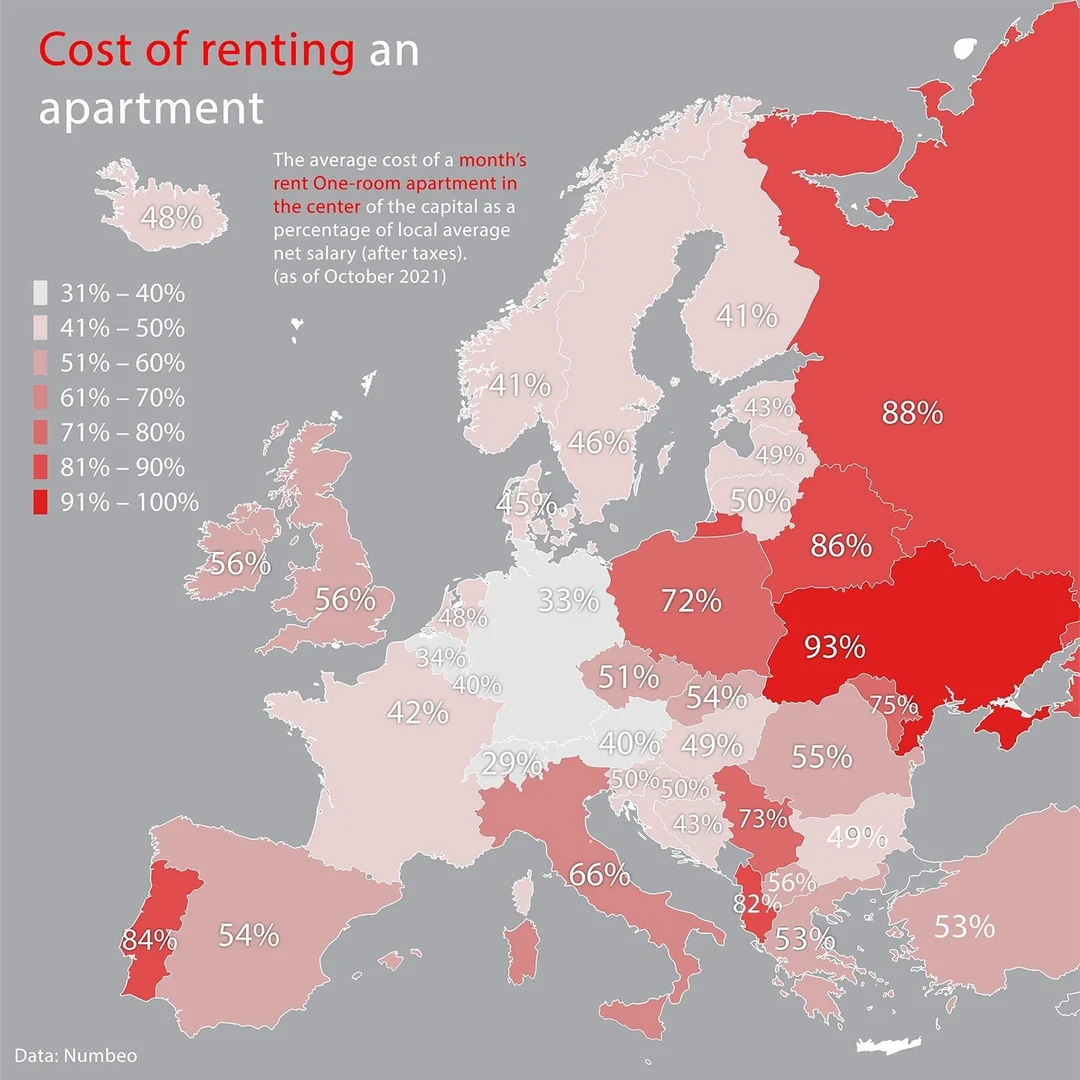

This problem is especially bad in the United States. But it's not only a problem in the US; it's a problem in many countries around the world — especially in Western countries in North America and Europe, whose economies have become financialized.

In the United States, for instance, the largest landlord is not an individual; it's a massive Wall Street investment firm: Blackstone, the private equity fund.

Blackstone owned more than 300,000 rental housing units in the US as of 2023. The number has only increased since then.

Blackstone and other Wall Street investment funds have been gobbling up residential housing. Then they ratchet up the cost of rent, which has fueled homelessness, as many people are being evicted from their homes.

By the way, the billionaire CEO of Blackstone, Stephen Schwarzman, who is the highest paid CEO on Wall Street, was one of the main funders of Donald Trump's 2024 presidential campaign.

Now that Trump has returned as U.S. president, this gives billionaire Stephen Schwarzman and Blackstone a lot of influence in Trump's policymaking.

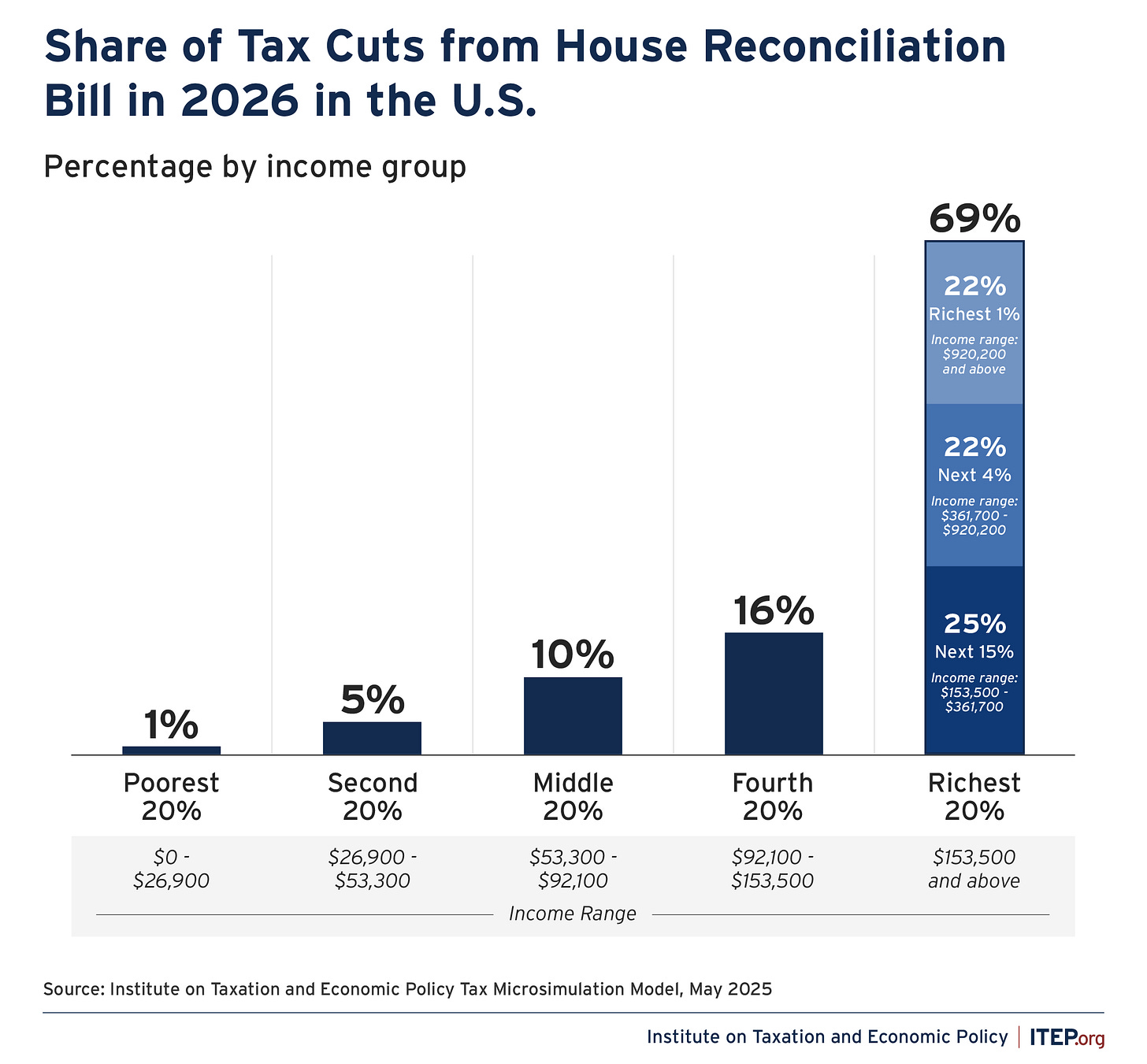

Of course, Trump has been massively cutting taxes on the rich — benefiting billionaires like Stephen Schwarzman, who helped to fund his campaign.

The US government is implementing many other policies that benefit these corporate landlords on Wall Street who are gobbling up houses all across the country.

Business Insider reported in 2022 that U.S. institutional investors bought 25% of the single-family homes flipped in the third quarter of 2022.

Flipping a home means an investor buys up a home — usually an old, dilapidated one — and then maybe invests a few thousand dollars in renovating it. Then they sell it, and they make huge profits of tens of thousands or even hundreds of thousands of dollars.

It's not just mom-and-pop people doing this. More and more, it’s institutional investors, many from Wall Street.

Business Insider reported that investors were behind 44% of the purchases of US single-family homes flips in the third quarter of 2022. And this problem is only getting worse.

CNBC reported that Wall Street financial firms have bought hundreds of thousands of single-family homes since the Great Recession, which Wall Street itself caused in 2008 and 2009.

That crisis also led millions of Americans to lose their homes in the first place. So Wall Street is responsible for so many of these problems.

CNBC recorded an incredible statistic, estimating, “Institutional investors may control 40% of U.S. single-family rental homes by 2030”.

These are the new feudal lords. These are corporate landlords that are gobbling up homes in the US.

The US government has played a role in supporting these private equity funds and other Wall Street firms that are buying up all of these homes — these Wall Street landlords.

CNBC noted that the “single-family rental industry got its start with government backing in the fallout after the 2008 financial crisis” — which, once again, was caused by Wall Street.

The CNBC report quoted the California congressman Ro Khanna, who said, “What’s outrageous is your tax dollars are helping Wall Street buy up single-family homes”.

The New York Times published an article that explained how Wall Street financial firms are buying up basically all of the residential homes in entire blocks in neighborhoods in the US.

The Times showed the example of a small neighborhood in Charlotte, North Carolina, called Bradfield Farms that has 34 homes. Investors have bought up 33 of those homes. All of them, except for one, now are owned by investors, who are renting out these homes. And, of course, they massively increase the cost of rent.

As the New York Times put it, “a newcomer is more likely to rent a house from a corporate landlord”.

The newspaper added, “Wall Street has come for the starter home”.

The New York Times looked at several different cities where investors are gobbling up residential homes, including Atlanta, Memphis, Orlando, Tampa, Las Vegas, Houston, and San Antonio.

This report noted that investors are largely targeting middle-income and working-class neighborhoods, especially with large Black and Latino populations.

So we see more and more that working-class Americans, in particular, Black and Latino working-class Americans, are now unable to own a home, because the houses are being bought up by these landlords, these investors, including corporate landlords on Wall Street, and they have to pay higher and higher rents to the landlord class.

This is a big reason why homelessness is exploding in the U.S.

Just in 2024, the official number of recognized homeless people increased by 18%, in one year. And that is very likely a conservative estimate, because a lot of homeless people don't go to shelters and are not registered as part of the system.

However, I should emphasize, this is not just a problem unique to the United States. This is happening in countries all around the world, especially in Western financialized economies.

A good example of this is Spain. The New York Times published another very interesting report looking at how, in Madrid, U.S. investment firms from Wall Street have also been buying up homes, over across the pond, across the Atlantic Ocean, in Europe.

I already talked about how the private equity fund Blackstone is the largest landlord in the US, with over 300,000 rental units that it owns.

Well, Blackstone has also become the second-largest owner of all houses in the country of Spain. And Blackstone is the single largest private owner of residential real estate in Madrid, the Spanish capital.

Blackstone owns 13,000 housing units just in Madrid, and nearly 20,000 rental units across all of Spain.

The New York Times reported that, “Across Spain, around 185,000 rental properties are now owned by large corporations, half of those by firms based in the United States”, largely on Wall Street.

And surprise, surprise, as these corporate landlords are gobbling up homes, rental prices have increased 57% since 2015, in a decade, and home prices have increased by 47% in Spain.

So what we are seeing is that landlords are taking over society, in the West in particular.

In order to discuss this today, I have the privilege of interviewing the renowned economist Michael Hudson, the author of many books, including Killing the Host: How Financial Parasites and Debt Bondage Destroy the Global Economy.

Today we talk about how capitalism has evolved from industrial capitalism into financial capitalism, especially in the neoliberal era, since the rise of the “free-market” fundamentalists like Ronald Reagan in the US and Margaret Thatcher in the UK in the 1980s.

They talk about so-called “free markets”, but, as Michael Hudson points out, when they say free markets, they mean the freedom of corporate landlords and Wall Street to buy up all of the existing assets, of monopolists to monopolize entire industries and extract monopoly rents.

Michael Hudson discusses how they are destroying the economy of the US and the broader West, and how people can fight back against these corporate landlords.

This is part two of a discussion that I held with Michael Hudson, based on an article that he published, titled “How the Global Majority can free itself from US financial colonialism”.

Now I am going to play some highlights of the main points that Michael Hudson made, and then we'll go straight to part two of our discussion.

(Highlights)

MICHAEL HUDSON: Rent is what John Stuart Mill said landlords make in their sleep. They make it without work. They do not play a productive role.

…

When modern economists talk about the “free market”, they're not talking about what Adam Smith and John Stuart Mill and the others talked about. They meant a market free from economic rent, free from the landlord class levying rents, that had to be paid out of the budgets of the employees.

…

One of the problems with the Global South countries, and the Global Majority, is they have sent their most promising students to the United States to be educated in economics. And the economic curriculum that is taught today doesn't talk about any of this kind of a free market, or the free market reforms as freeing economies from economic rent.

There was a counter-revolution in the United States and Europe against the industrial-capitalist reforms. The rentiers fought back.

…

What China did that the other nations, the Western nations, didn't do was it completed the industrial capitalist revolution by keeping banks and money creation in the public domain.

So in China, it's the People's Bank of China that creates money and determines who is going to get the credit and on what terms.

That's not the case in the West. In the West, it's the commercial banks that determine who is going to get the money and create credit for.

All they're concerned about is making the quickest gain possible. And the quickest gain is possible by lending money to a corporate raider, to take over a corporation, essentially splitting it up in parts, selling off its real estate, and leasing it back, using the sales price as a special dividend.

Corporations will borrow even to buy their own stock. They'll borrow at low rates under quantitative easing, and buy stock yielding a higher rate.

The Western banks are in unproductive lending, and China focuses on productive lending.

(Interview)

BEN NORTON: Michael, it's always a real pleasure having you. Thanks for joining us today.

So, Michael, this is the second part of our discussion. In the first part, we discussed the idea of “U.S.-centered financial colonialism” that you discussed in your article.

You talked about ways in which countries can create alternatives in a more multipolar world, and how, in particular, they can challenge the debt that they're trapped in; and how, ultimately, it's impossible to pay off this large dollar-denominated debt, so they shouldn't pay it; instead, they should seek alternatives.

Here, in part two, we're going to talk about how landlords are taking over society and making the cost of living prohibitively expensive for working people.

In order to understand why this is happening, we have to understand the idea of economic rent, and how it's different from value and profit.

Let's just start with a very broad question. Can you explain why you felt it was important to write this article? You described it as almost a kind of manifesto of sorts. And what is the main argument you're making about how the Global Majority can free itself from US-dominated financial colonialism?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, I wrote the article because there is a tendency for the Global Majority, and especially for the Global South, only to go halfway, and not to confront the fact that, for the last 200 years, ever since the industrial revolution, the whole dynamic of the industrial nations — Britain, France, Germany, and the United States — has been revolutionary.

They got rid of their vestiges of feudalism. They got rid of the rentier class. They defined the free market as a market free from economic rent, land rent, monopoly rent. And they wanted to reform finance. And they did many of these things.

But in their foreign investment, from the early 19th century on, they wanted other countries not to protect their industry, but to supply the industrial nations with raw materials, and essentially to let the countries running trade surpluses, the industrial nations, use these surpluses to obtain the money to lend to the raw materials producers and invest in their land, and natural resources, and public infrastructure.

So what was created was a mirror-image economy. You had the world divided into two kinds of economy: a reformist, industrial capitalist economy in the industrial nations; and rentier economies, largely foreign-owned, as the rentiers were foreign, in the whole rest of the world that did not protect itself, did not have governments strong enough to support their own industry, because of the foreign domination.

These countries have never been able to go beyond the residue of foreign colonialism and financial imperialism, we can call it. And what they face is very much the same kind of problem that Britain and Europe faced: How do industrial capitalists minimize their cost of production by getting rid of all of the rentier overcharges? By essentially having the government pick up many of the economy’s charges, by freeing the economy from monopolies; by taxing income progressively, especially raw materials income and land income.

Just the opposite is the case with the the Global South countries. Foreigners own their raw materials. Foreigners essentially have been able to use debt leverage to say, well, we will use the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, in the United States, to lend you money so that you can afford to finance your trade deficits that come from your not industrializing.

But this lending is going to be on terms that enable us to buy up your industry, to privatize your public domain, to privatize your natural monopolies, and charge monopoly rent, instead of providing public services, health, education, communications, transportation at a subsidized rate to help make a competitive industrial economy.

Unless the Global Majority, and especially the Global South countries, restructure their economy in the same radical way that Europe restructured its economy, it is not going to be able to escape from the existing specialization of world labor, and investment, and economic dependency.

That's really what it's all about. What is needed in terms of domestic policy for countries to be sovereign and really independent, instead of having to spend all of their tax revenues and reorganize their economy just to pay their foreign dollar debts and enable the foreign investors to send all the land rent, and natural resource rent, and monopoly rent out of their countries, to the industrial creditor nations.

BEN NORTON: Thanks, Michael. That was a great summary of your main argument.

Let's talk more about this idea of the rentier class. You point out that the classical political economists, people like Adam Smith and David Ricardo, who are so often cited by mainstream neoliberal economists today, they often don't really read those political economists’ work.

If you go back and read the classical political economists, you see that they were viciously critical of the landlord class, and they saw these landlords as remnants of the feudal aristocrats, who used their control over monopolies, natural monopolies and land, in order to charge monopoly rents. They didn't produce anything; they didn't contribute anything productive to the economy.

Here are some quotes from Adam Smith in his magnum opus, The Wealth of Nations, written in 1776 (emphasis added):

“As soon as the land of any country has all become private property, the landlords, like all other men, love to reap where they never sowed, and demand a rent even for its natural produce” (Book 1, chapter 6).

“The landlord demands a rent even for unimproved land, and the supposed interest or profit upon the expence of improvement is generally an addition to this original rent. Those improvements, besides, are not always made by the stock of the landlord, but sometimes by that of the tenant. When the lease comes to be renewed, however, the landlord commonly demands the same augmentation of rent, as if they had been all made by his own” (Book 1, chapter 11).

“The rent of land, therefore, considered as the price paid for the use of the land, is naturally a monopoly price. It is not at all proportioned to what the landlord may have laid out upon the improvement of the land, or to what he can afford to take; but to what the farmer can afford to give” (Book 1, chapter 11).

For the classical political economists, landlords were differentiated from industrial capitalists — who, yes, were exploiting labor. And this is something that Karl Marx, of course, emphasized later on, the surplus value extracted from workers.

However, there's this idea that Marx was completely different from the classical political economists like Adam Smith. But, in reality, Marx had much more in common with Smith and Ricardo than do today's neoclassical, marginalist economists, who do not support the labor theory of value — whereas Smith, Ricardo, and Marx all agreed on the labor theory of value, that value ultimately comes from workers producing something.

So the rentier class does not produce anything. And this is why the classical political economist saw the industrial capitalists as revolutionary compared to the landlords.

Even Marx himself. Go read the Communist Manifesto. The beginning of the first chapter praises capitalism as a revolutionary force against feudalism.

The bourgeoisie, historically, has played a most revolutionary part.

The bourgeoisie, wherever it has got the upper hand, has put an end to all feudal, patriarchal, idyllic relations.

…

The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production, and thereby the relations of production, and with them the whole relations of society.

Your argument, Michael, is that, with the increasing financialization of capitalism, capitalism has moved away from that progressive element that maybe was true in the very early days, and has become more and more monopolized, with less and less competition, less and less actual productivity, less and less innovation, and more and more exploitation, and more and more extraction of monopoly rents.

Can you talk more about this idea?

MICHAEL HUDSON: Yes, it's more complicated than that. The term labor theory of value is very misleading. It's really a labor theory of economic rent.

What we're dealing with, and what the classical economists all had in common, leading up to Marx, and later to Thorstein Veblen and other people, was a theory of value, price, and rent.

Price was the excess of value, which is the basic cost of production. Value was defined as what does an economy need as a necessary cost of production to the industrialist? And how much is unnecessary?

Well, what Marx described industrial capitalism as doing, looking back on the 100 years just before he wrote, was that the capitalist wants to get rid of all the unnecessary costs of production, the costs that are really not part of nature, not real costs, but they’re legal costs — the legal right for landlords to charge rent, instead of having the rent collected by the state as its natural tax base, which is what Adam Smith, and [David] Ricardo, and John Stuart Mill, and most of all Marx and the socialists developed.

The whole idea of value and price theory was to bring prices down to the actual value, the cost of production.

Calling it the labor theory of value meant that, ultimately, the real cost of production is labor.

Land was produced freely, by nature. There is no cost to production for land, but landlords charge for it.

Monopolies are created by laws. They're not natural. They are monopoly privileges, often that were created in the medieval period by governments, with the help of their bankers, to figure out a way of extracting monopoly rents from the economy, to raise the money to pay interest on the war debts that the European kingdoms took on.

Banking also does not have to be privatized and run for the benefit of creditors.

As a matter of fact, Adam Smith — apart from Ricardo, who was a bank spokesman — almost all the economists from the middle 18th century wrote about how banks did not lend for industry and development; they didn't provide James Watt with the money to build those steam engines. He had to take a mortgage out.

Especially English and American banking didn't lend for industrial purposes; it was usury banking. It was lent mainly for rent-seeking powers, to buy rent-seeking property like land, or monopolies — like foreign railroad investment was the most important thing in the 19th-century stock market.

Communications, port development, road development were were all things that were financed, that were added to the cost of production, all sorts of monopoly charges that the classical theory of value, price, and rent wanted to get rid of.

When, modern economists talk about the “free market”, they're not talking about what Adam Smith, and John Stuart Mill, and the others talked about; they meant a market free from economic rent, free from the landlord class levying rents that had to be paid out of the budgets of the employees.

As long as land was owned by the landlords, and as long as the landlords, especially in Britain, imposed special agricultural tariffs, such as the Corn Laws — that prevented Britain from importing low-priced food to feed the labor, so that they could make higher agricultural rents on their land, yielding very high-priced costs — there was no way that Britain could have competed with other industrial countries.

That was the whole theme of David Ricardo. Even though he was a spokesman for the bankers, he criticized the landlord class, because, if England would protect its landlords, its landowners, then England would not be the workshop of the world. And if England were not the workshop of the world, then British bankers would not be able to make profits and interest on their major market, which was financing foreign trade and foreign-exchange transfers.

So the whole idea of the industrialists and the banking class, working together, was to get rid of the land rents and monopoly rents, to make Britain so much more streamlined and competitive, by bringing its prices down to the actual cost value, by getting rid of the economic rent, so that they could underproduce other countries.

Then, by supporting free trade instead of agricultural protectionism — and this was at a time when the landlord class still controlled the House of Lords, the upper house of government, and was able to dictate its own self-interest — the whole idea was that parliamentary reform to free politics from the landlord class enabled the reformers, the industrialists and the bankers, to free markets from the power of the landlord class to impose rents, the power of the monopolists to charge high rates, by getting rid of the monopolies, by enforcing competition, such as the United States did in with its anti-monopoly laws.

Countries such as Germany, at the end of the 19th century, transformed banking. Instead of letting banks lend money for unproductive purposes, for basically what Marx called usury banking, Germany took the lead in industrializing banking, and making money creation and bank credit focused on financing capital investment in industry, which is what enabled Germany to rise so rapidly to become an industrial power.

Well, none of this occurred in foreign countries. Britain adopted free trade and made a political deal with other countries when it abolished the Corn Laws in 1846, and it told the United States, Latin America, and other countries, “We will let you into the British market, without tariffs, if you let us into your market. Why don't you buy it in the cheapest market? We have a head start. We spent a hundred years, giving ourselves a head start and reforming our economy so that we can provide you with industry much cheaper. Why don't you export your raw materials in exchange for our industry? It will be one happy, unified world economy. Everybody produces what they are best at”.

David Ricardo made a mathematical example of British cloth exchanging for Portuguese wine. And in Ricardo's example, he was so dishonest, so rhetorical that he made Portugal, the raw material supplier, the “winner”, in the gains from trade.

The kind of international trade theory [of comparative advantage] that is taught, even down to today, is all based on Ricardian free-trade theory. It leaves out of account the political dimension, the social dimension, the whole idea of what is the role of economic rent in determining international price structures and competition.

Well, one of the problems with the Global South countries, and the Global Majority, is they have sent their most promising students to the United States to be educated in economics. And the economic curriculum that is taught today doesn't talk about any of this kind of a free market, or the free market reforms as freeing economies from economic rent.

There was a counter-revolution in the United States and Europe against the industrial capitalist reforms. The rentiers fought back.

By the late 19th century, you had John Bates Clark in the United States, you had the Austrians in Europe, and the British sort of liberals, all saying, “Well, there's really no such thing as economic rent. There is no difference between price and value. Whatever a good or a service is sold for is what actually consumers decide to pay. It's all consumer demand for everything. Everybody earns whatever they get. There's no economic rent”.

That is what students are taught here. And then they go back to their countries. And there's a belief in these countries — I've even seen it in China, where, my students there complain that students educated in the United States are given preference in jobs, but they certainly don't learn Marxism in the United States.

The only group that is still talking about Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill, Ricardo, and the whole classical economics school, were the Marxists, because all of this logic of value, price, and rent sort of culminated in Marx, who really was the patron saint of economic accounting.

He actually worked on the balance sheets of industiral companies, and made a model of the economy. And in this model, he distinguished industrial capitalism from what went before, from the feudal time, basically, and from the rentiers.

He said, Adam Smith was right. John Stuart Mill was right. Rent is what John Stuart Mill said landlords make in their sleep. They make it without work. They do not play a productive role. And the economy is divided into two halves: the economy of production and the economy of circulation.

Now, it's true, as you pointed out a few minutes ago, that the industrialist does sell the products that his employees make; he sells these products of labor at more than it costs him to hire the labor force.

But Marx said this is creating value. The industrialist actually organizes production. The industrialist doesn't make profits in his sleep. He organizes a supply chain of raw materials. He develops markets, and a whole marketing system. He organizes industry. He modernizes other means of production, constantly.

So Marx included industrial profits as an element of value, and he said, if you look at the production part of the economy that produces value, that will certainly include industrial profits, but it will exclude land rent, natural resource rent, monopoly rent, and financial interest, that is made just because banks have bought the monopoly power to create money and credit, that's accepted as legal tender for payment of taxes. This is a legal creation that is not necessary.

Well, just imagine if you were making a model of national income and product account, or the gross domestic product, the United States and Europe, all the countries in the world under the United Nations, sort of formatting of gross domestic product, they include land rent, and financial services, and monopoly rent in this.

In the United States, for instance, I tried to separate rent seeking from the actual real value of the GDP from the excessive economic rent in the GDP. I asked the Department of Commerce, when a bank imposes late charges of 20% or 30% on credit card users, raising their interest charge from 19% to over 30%, where does this appear in the GDP?

They said, oh, that's providing a financial service. So it's considered as a service.

Well, the classical economist said monopolists, bankers, and landlords don't provide a service. They have a special privilege of obtaining money. But that's not a product. Late fees are not a product. Receiving interest and receiving income from the interest you get is not a profit.

Rising housing prices that really are just the increase in the price of land, not of building, but the price goes up despite the fact that the building stays what it is; all of that is not a product; it's essentially financial price inflation.

The rent of this location that is going up, the land rent, is used to pay interest to the banks. And so the United States and Europe got rid of a feudal hereditary landlord class. We don't have a landlord class anymore. We have democratized housing and commercial real estate. Anybody can buy a house, buy commercial real estate. But most people have to do so by taking out a mortgage.

And how do they get a mortgage? They bid against each other, and the winner is the buyer who promises to pay the most of the land rent and other rental income to the bank as interest.

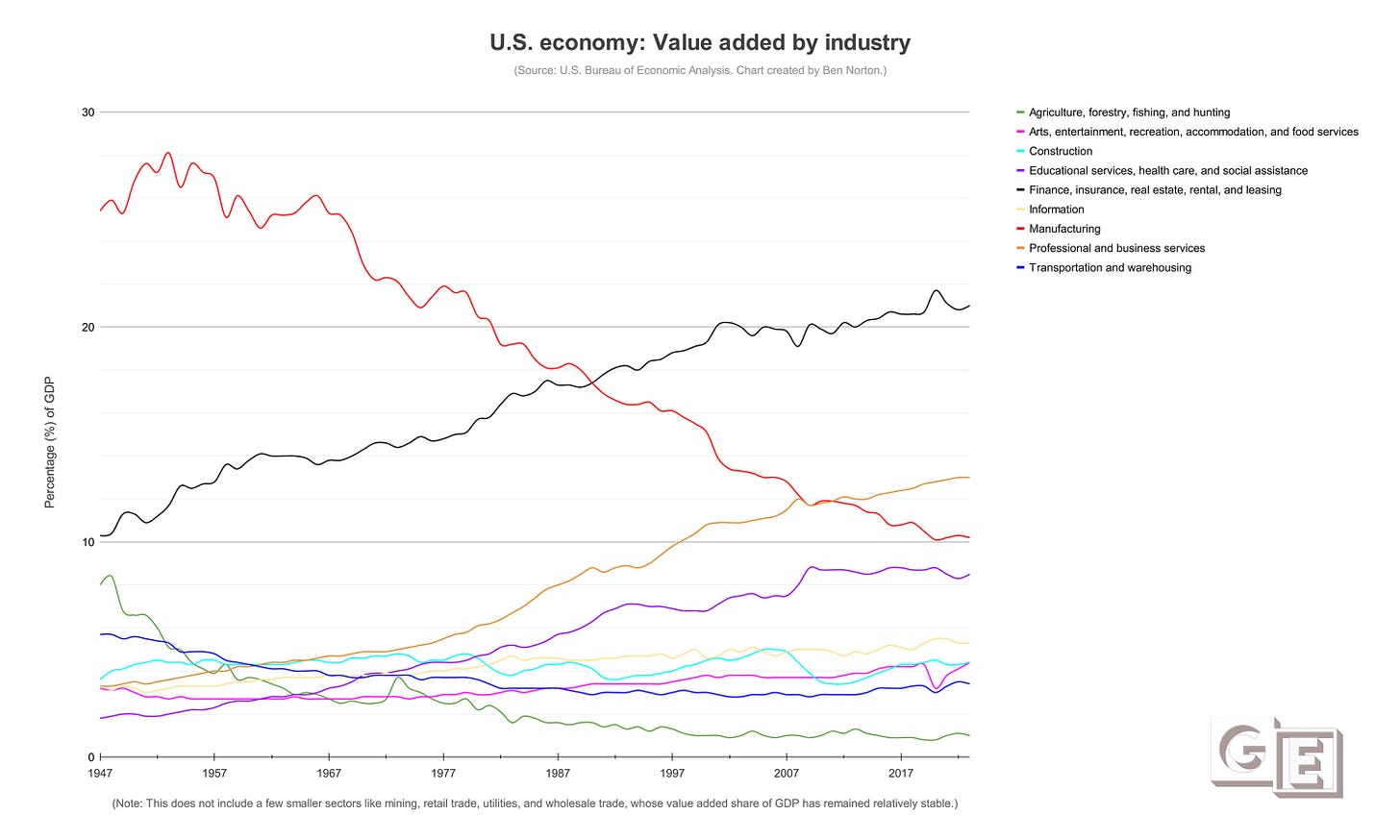

So you have somehow had the Western economy turn into a rentier economy, and that has led to deindustrialization.

Unless the Global South countries and Global Majority countries do what Britain, France, Germany, and America did in the 19th century, or what China did after the 1949 revolution, they're not going to be able to have an economic alternative that is going to enable them to be competitive industrial powers, in charge of their own income.

Instead of transferring all of the economic rent in their economy to the foreign owners, to the foreign investors in their mining, their oil industry, their public infrastructure, that's all developed and has left them with this whole superstructure of foreign debt, that prevents their governments from investing to support the economy; to invest in their own, new infrastructure to serve the economy, instead of roads and ports for foreign investors.

There's a whole structural revolution in the organization of the economy and society that is needed here, just like the whole parliamentary political system in Europe had to be restructured, in order to introduce the economic reforms that made the industrial nations so much more efficient, and the countries they invested in so much less efficient.

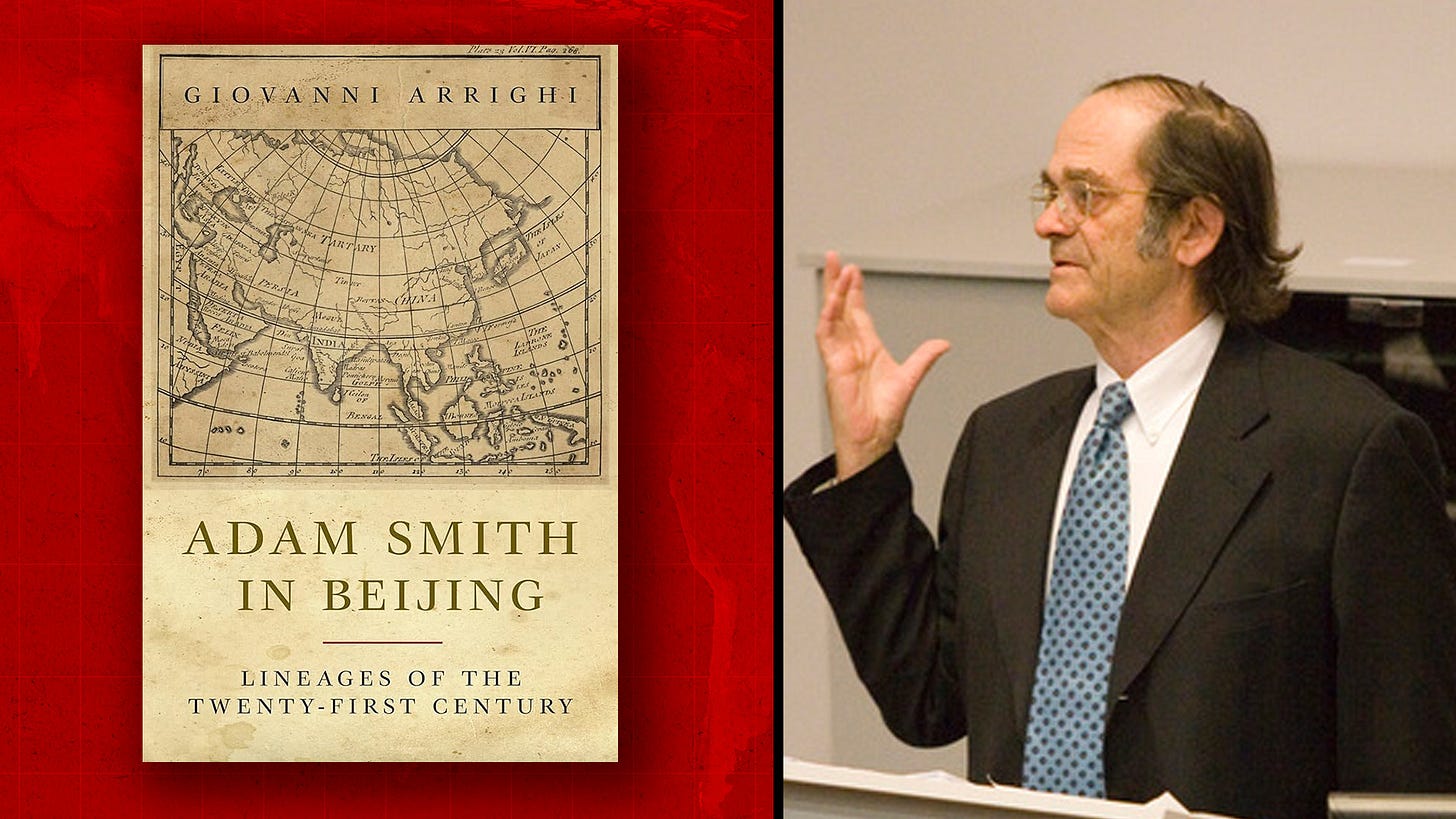

BEN NORTON: Very important analysis there, Michael. What you said there reminded me of the work of Giovanni Arrighi, the political economist who unfortunately passed away in 2009.

In 2007, he wrote a very interesting book, right before the U.S. caused a massive financial crisis, which was Adam Smith in Beijing.

In this book, he argued that, again, that Marx was critiquing Adam Smith, but actually there was much more in common between Smith and Marx than with many neoclassical economists today.

Arrighi described the idea of what he called “Smithian socialism”, or a kind of market socialism, which is very similar to the Chinese model today, which includes public ownership of the commanding heights of the economy, the natural monopolies, land, resources, telecommunications, infrastructure, and, most importantly, finance; but also a robust internal market economy, with lots of competition that drives down profit margins.

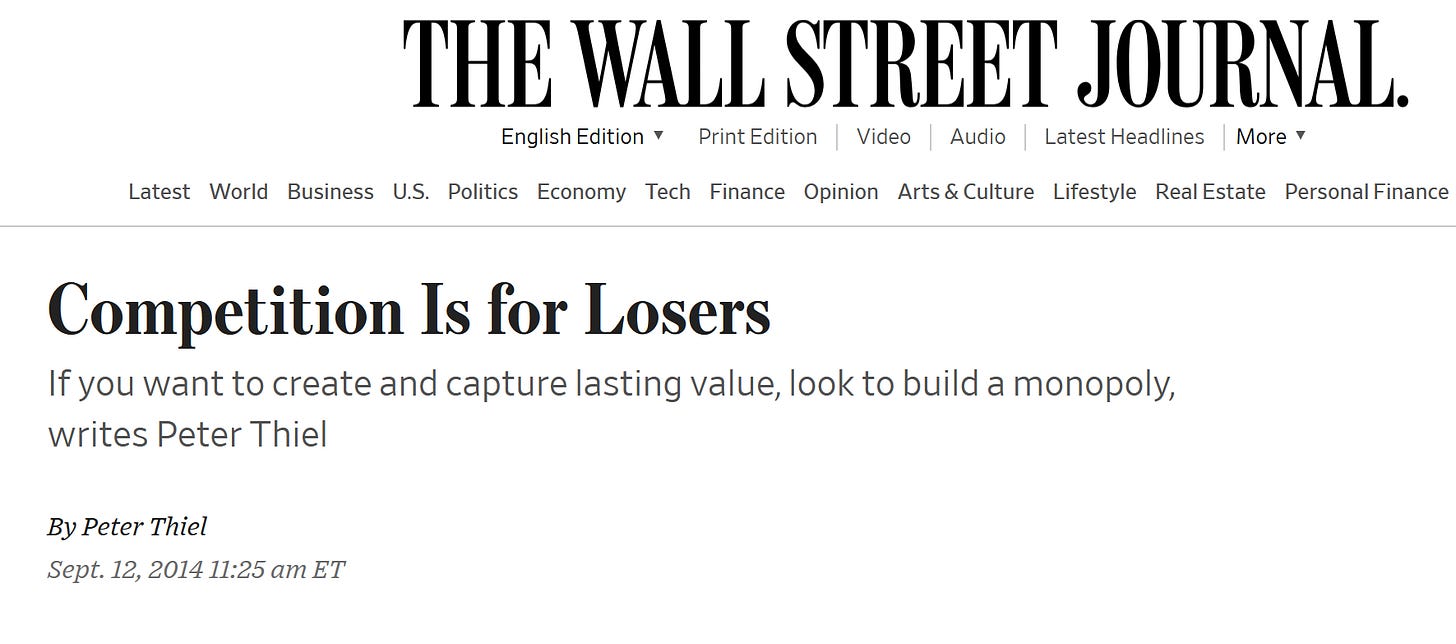

Because, as you pointed out, the original, classical political economists like Smith recognized that, if you have perfect competition, profits go to zero. And actually, capitalists in many ways are incentivized to monopolize their respective industries, so they can maximize their profit margins.

Today we actually see this expressed pretty openly, by people like Peter Thiel, who is a major supporter of Donald Trump.

Peter Thiel is a billionaire from Silicon Valley, a major venture capitalist. And he also employed U.S. vice president JD Vance.

Peter Thiel, for years, has argued in defense of monopolies. He published an oped in The Wall Street Journal titled “Competition Is for Losers”, in which he lamented the fact that, if you do have lots of competition, profit margins fall to zero. He said that that's why all capitalists want a monopoly, and he argued that's a good thing.

Whereas, you look at China's socialist market economy today, you actually have all these capitalists are, you know, engaged in blood sport. They're all fighting each other to the death in this cutthroat competition.

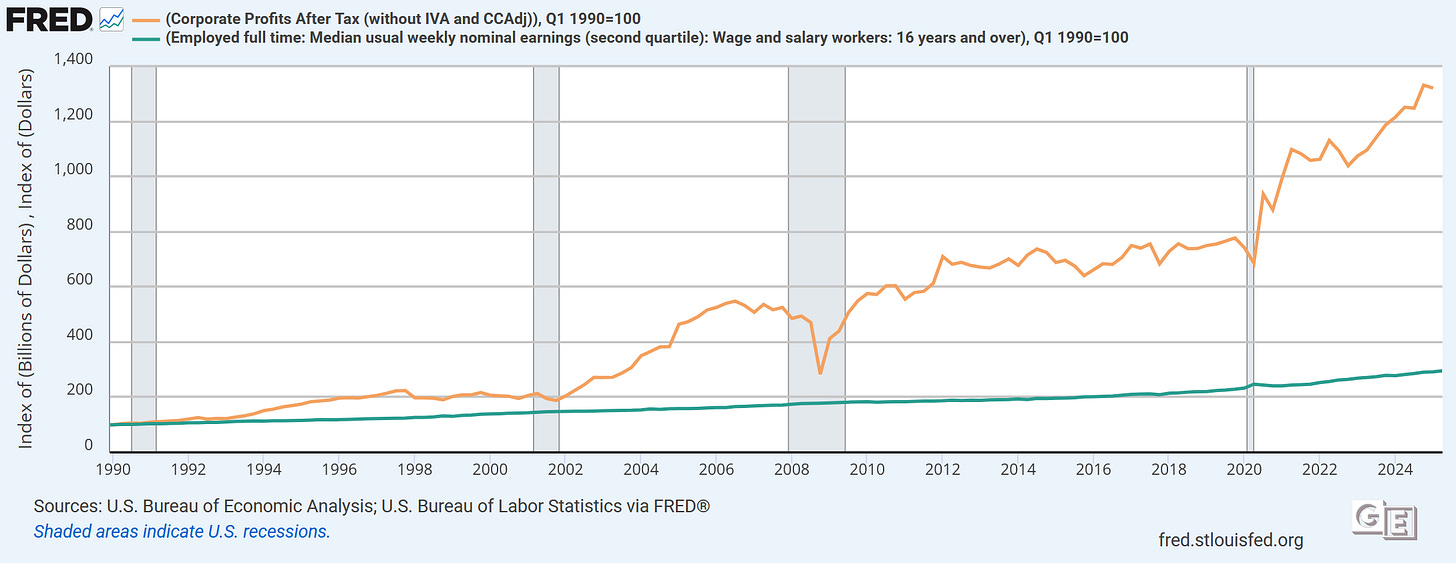

Profit margins are basically going to zero in China, whereas in the US, the profits of corporations are at an all time high — and the labor share of income is falling and falling, as corporate profits are at an all time high.

So this to me seems to be empirical substantiation of exactly what you're arguing about, how, when you have this monopolized system, like in the US, you have very high profits.

When you have this system in China that guarantees competition and minimizes monopolies, you have very low profits.

And it's clear which system is actually providing a better standard of living for its people.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, Arrighi’s big point is quite correct, but his title for it, Adam Smith in Beijing, is very unfortunate.

What actually happened was, in the late 1970s, the Chinese decided, we don't want our kind of socialism to be what Stalinism had in Russia.

I was asked, initially, do you want to go to this Shanghai institute that was having the Chicago school people go, Milton Friedman and his colleagues. I said, “Gee, that sounds pretty wonderful”.

This was like 1979. And I said, “You know, it probably helps that I'm a Marxist. I grew up in a Marxist household”. And they said, “Oh, dear, you better not go. They don't want any sign of Marxism”.

Well, what happened was that Milton Friedman went, and he convinced them to let a hundred flowers bloom. He said, “You can't have the state design everything. You have to leave room for innovation to occur”.

That's what happened in Britain, and happened in Germany.

BEN NORTON: I'm sorry to cut you off, Michael. Definitely, you are right that in China, they did have this idea of let a hundred flowers bloom. And there was a lot of pragmatism and experimentation.

But just on the specific issue of Milton Friedman, this is often misunderstood. And David Harvey did a lot of damage with this false idea that China adopted neoliberalism and they listened to Milton Friedman.

Actually, this is described very well in the book How China Escaped Shock Therapy by Isabella Weber. She looks at the archival evidence from China and shows how, yes, you're right that Friedman did go, along with many other economic advisors from all around the world, because the Chinese leadership, led by Deng Xiaoping at that time, wanted to hear many different opinions. So Milton Friedman was one among thousands of different economists who was invited.

But actually, in her book, Isabella Weber showed that they largely ignored what Milton Friedman recommended, and instead listened to the advice of other economists who were not extreme neoliberals like Friedman.

So, for instance, on the issue of price liberalization, Friedman called for a “big bang”; he wanted liberalization of all prices immediately.

Weber shows in her book how actually the Chinese government had an incrementalist, gradualist approach, and they did not adopt the “big bang” theory; they did not adopt that approach of Friedman.

MICHAEL HUDSON: You're quite right. I just cited him because he's the most well known. And, of course, he's such an extremist that any realistic person would realize that he's almost a nutcase.

What China did that the other nations, the Western nations, didn't do was it completed the industrial capitalist revolution by keeping banks and money creation in the public domain.

So in China, it's the People's Bank of China that creates money and determines who is going to get the credit and on what terms.

That's not the case in the West. In the West, it's the commercial banks that determine who is going to get the money and create credit for.

All they're concerned about is making the quickest gain possible. And the quickest gain is possible by lending money to a corporate raider, to take over a corporation, essentially splitting it up in parts, selling off its real estate, and leasing it back, using the sales price as a special dividend.

Corporations will borrow even to buy their own stock. They'll borrow at low rates under quantitative easing, and buy stock yielding a higher rate.

The Western banks are in unproductive lending, and China focuses on productive lending.

However, the one thing that China does not do is what Adam Smith urged most of all. He said, you've got to avoid land rent. Land rent is the natural public source of tax revenue. It's the natural tax base, not taxes on labor’s wages or industrial profits, but the land.

Well, Marx, spent volume one of Capital talking about what you and I were just mentioning: How does a capitalist make his profit productively? By employing labor to produce a surplus, to produce profit, the surplus value in this.

That's how Marx explained, well, what is the labor theory of value? Are we referring to the price that labor received for its wages, or the price at which labor’s product is sold for? There's a surplus over and above value there. Marx did not call that surplus economic rent; he said it's still value, but it's profit, not rent.

In order to understand that, you have to understand the whole economic body of economic discussion for the hundred years leading up to him, from Adam Smith and Ricardo, Malthus, Mill, all of that. That is what is not taught here.

After Marx said, well, here's what I'm adding to classical value theory, he then spent volumes two and three of Capital discussing rent and financial returns. And he essentially wrote what used to be called volume four, which he had originally meant to be the first volume of Capital, in his theories of surplus value, which was really the first history of economic theory that was published in the West.

Marx, in his theories of surplus value, discussed all of the development of economic thought regarding value, price, and rent theory, from William Petty through Davenant and the Physiocrats, and all of the minor economists, whose names probably are unfamiliar to most of your audience.

Well, the Chinese that I've spoken to, and I was a professor of economics at Peking University, at the School of Marxism Studies, so I'm pretty familiar with what they taught.

I was invited to the first international Marxist conference, and I said, in order to understand Marxism, you have to read volumes two and three of Capital, and theories of surplus value as well. Well, that didn't go over very well, because I was focusing on economic rent.

I said, we're seeing an increase in housing prices in real estate. And the problem is the relationship between China's central government and the localities. A part of their, you know, let a hundred flowers bloom philosophy is, well, let's let each of the villages and the towns develop their own organization, and we'll see what develops the best.

Well, a common denominator in the Chinese localities is they finance their public spending by selling, or leasing, land to real estate developers. And the real estate developers buy this and develop into housing. And over time, this housing is sold at rising prices.

This rise in housing prices, or commercial real estate prices, is really an increase in land rent. It was the increase in price that John Stuart Mill was referring to, when he said landlords make profits in their sleep. He meant landlords make what today are called capital gains, which are really rent valuation gains, in their sleep.

Well, China has not has not specifically addressed this rent problem that underlies the strains in national and local finances, that led to the whole real estate crash of overbuilding.

Well, at the second Marxist conference, David Harvey came. I gave one of the special speeches at the first conference. David Harvey was given the corresponding keynote speech at the second conference, because his books have sold very well in China.

And Harvey said, all you have to do is just what Michael Hudson said: you have to read volumes two and three of Capital in order to get the full Marxist grounding.

With Adam Smith and classical economics, it's all one evolving system that explains why Europe developed and the rest of the world didn't — apart from the United States, that was the other protectionist industrial nation, that became a creditor nation as a result.

Well, David Harvey did not receive any more of a positive response than I received. And there's a hesitancy in China to study volumes two and three of Capital, just as in the United States, there's no discussion of classical economics; there's very little.

What China has done in a way you could say is to reinvent the wheel spontaneously, just by the internal logic of economic development.

China has replicated the policies of Britain, France, Germany, and the United States, and industrial capitalism itself.

It has replicated it above all by preventing monopolies, and by preventing a banking sector that has become what it was in America, the mother of trusts, by creating monopolies and funding, and lobbying for the creation of monopolies — which you have under Donald Trump's regime so far in the United States.

Under Trump, for the last half year, he has abolished almost all implementation of America's anti-monopoly legislation.

Well, China has done almost every prevention of rentier income, economic rent, except that of land rent, which is why so many absentee owners of real estate have developed in China, buying a property in order to rent it out as landlords.

That's what led President Xi to say, housing should be for living; it shouldn't be an investment vehicle.

To the extent that land is an investment vehicle, it is because of land rent that is not being collected as the tax base.

Well, China will say, well, we really don't need a tax base, because we can create our own income. We don't need to borrow from a financial class, because when there was a revolution, in 1945-49, we got rid of the landlord class; we got rid of the financial class.

So the government had to just survive by creating its own money, just like the United States created greenbacks during the Civil War, for instance; or the American colonies created their own currency.

This is universal. China just followed the logical path of least resistance, without any opposition from a rentier vested interest that said, “No, no, you have to make money most easily by economic rent, not by industrialization, not by investing”.

That was really China’s advantage. But it didn't follow the number one emphasis of Adam Smith on land rent.

BEN NORTON: Again, Michael, you raised so many interesting points there. It's hard to know which exactly to respond to.

I want to raise this interesting idea that we've seen become this kind of trope that is very popular in social media today, on finance TikTok and Twitter, which is the idea of “passive income”.

I'm sure you've seen this. And what's actually quite funny is you've often cited this very important quote from the 19th-century political economist John Stuart Mill, who said:

“Landlords grow rich in their sleep without working, risking, or economizing. The increase in the value of land, arising as it does from the efforts of an entire community, should belong to the community and not to the individual who might hold title”.

Now, when you see the full quote, it's clear that he's saying that these landlords should not be receiving this rental income that they get, this rent extraction from simply owning this land and monopolizing this land.

But what's hilarious, in a kind of sadistic way, a very sad way, is if you look up the quote, “Landlords grow rich in their sleep”, from John Stuart Mill, you can find many social media posts from realtor companies, different realtors quoting that and saying this is why you should buy a house and you should become a landlord.

Especially for younger people, there's this big trope of “passive income”. There are millions of videos on social media of people trying to teach you how you can earn passive income by becoming a landlord.

In the US economy, so much revolves around this idea today of everyone trying to become their own landlord, so they don't have to work, and this is seen as something positive. But obviously this is extremely destructive for society and the economy.

It's also a side product, a byproduct, of the fact that the economy has been completely financialized, and people feel like they have no economic alternative, so they all just want to become a landlord.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Well, this is what's taught in business schools. This is how to make money. This is what is taught in the economic curriculum.

So just imagine if the Global South countries send their students to the United States — very often the students of the wealthiest families, that can afford to pay the $50,000 to $80,000 a year that it costs for a prestige US university — you can imagine what happens when they go back to their country.

They are not taught about how to create an economy that is rent free, but you get an economy that provides a free lunch — income without working, a free lunch economy.

Milton Friedman said “there is no such thing as a free lunch”, but a free lunch is what finance capitalism is all about. It wasn't what industrial capitalism was all about.

But we've turned into the free lunch economy, without the academic curriculum taking note of this, and without the whole official statistical picture of economists drawing a distinction between real GDP, the actual cost of production sector; and fictitious GDP, the economic rent.

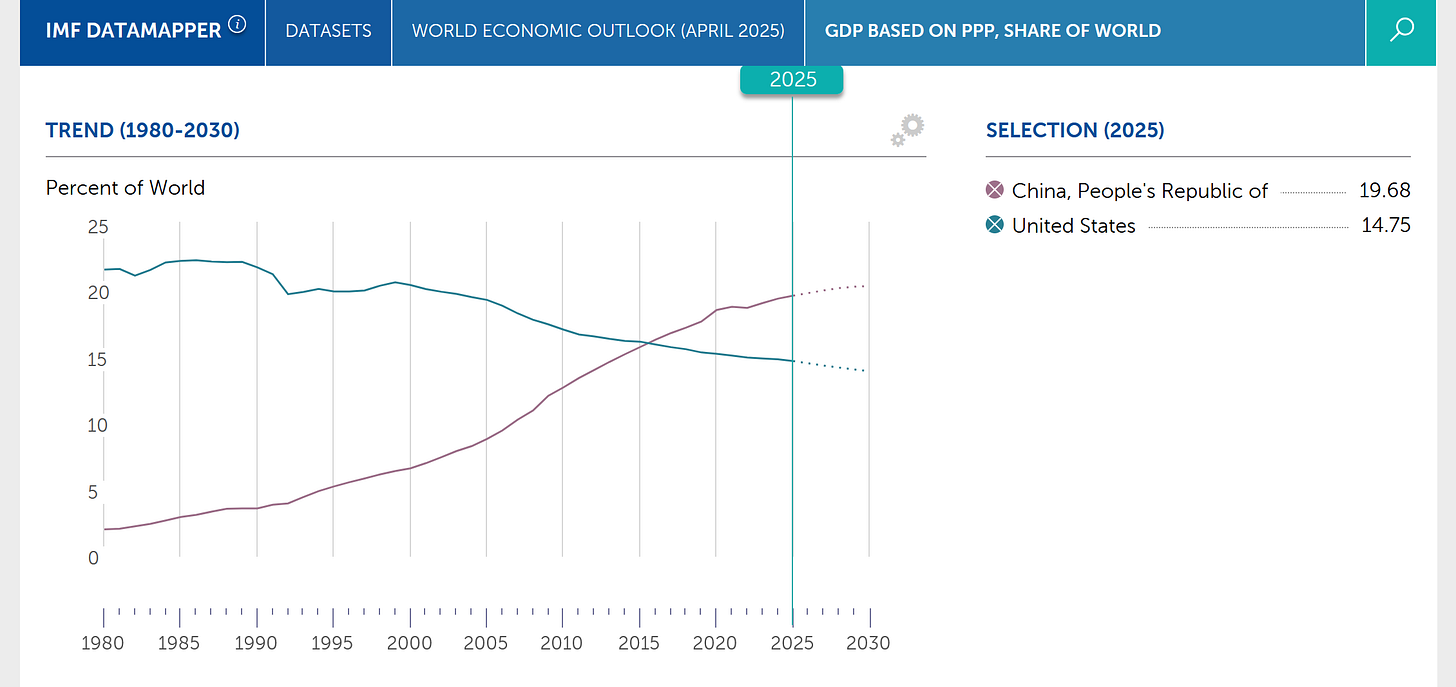

Well, what this means is suppose you're comparing China's GDP to the US GDP. That's misleading. Of course it shows China in the lead there, but the lead is actually much faster than the statistics show.

Because if you say, well, what's the comparison between the real GDP of the United States and the real GDP of China, in terms of what's actually produced, China is way ahead, because it doesn't have the fictitious GDP that the United States and the Western economies have.

The only fictitious element is the increase in real estate prices, which is an increase in price, not value. And to do that, you have to have the classical distinction between value, price, and economic rent.

That simple distinction is so easy to say in words, but, generation after generation, there were debates to refine what that meant, refine the concept.

What's the necessary cost to production? What's an unnecessary cost to production? What's value, and what's price in excess of value? All of this took a hundred years to develop.

And after it developed, by the late 19th century, as I said, the rentiers fought back and introduced a century of junk economics, the Chicago School, the “free-market” economics that became a free market for the rentiers, not for the rest of the economy.

BEN NORTON: Michael, I think that's the perfect note to end our discussion.

This was part two of my interview with the economist Michael Hudson. This-two part discussion is about Michael's article titled “How the Global Majority can free itself from US financial colonialism”.

In part one of this interview, Michael discusses the development of this system he describes as “US-centered financial colonialism”, how it developed, what institutions make up this system, and how countries in the Global Majority can develop alternatives to this system.

So with that said, Michael, any last thoughts you want to add here?

MICHAEL HUDSON: No, you've said it all.

BEN NORTON: All right, well, thanks for joining us, Michael.

Michael Hudson is a world-renowned economist and the author of many books.

Thanks a lot, Michael. It's always a pleasure.

MICHAEL HUDSON: Thanks for having me.

In Upton Sinclair's classic, The Jungle. the Jurgis Rudkus family bought a house that was flipped, and when they lost it, it was flipped again. In essense, that is what corporations are now doing to rental property, driving rents continually upward, and increasing homelessness. Will it drive the working class to do what was done in the French Revolution, and behead the aristracy through the passing of common sense working class oriented laws?

So we are living the neoliberal nightmare that has been around for fifty years. Many years ago I read Robert W. Mchesney's definition of neoliberalism as the introduction to Noam Chomsky's book Profits over People. It was obvious there would be hell to pay. There has been a huge amount written about the negativities of neoliberalism and never part of the political dialogue . Another conspiracy of silence ruining our societies. The political idiocracy and the MSM have been co-belligerents in the massive betrayal.

Are we to conclude that passivity, stupidity and complacency are the death knell of Western Civilization.